No Sex Please We're Brutish: Subversion in 'Brief Encounter'

I'm going to try and arrange letters in such a way that you'll get an idea of why I think Brief Encounter (David Lean, 1945) is one of the greatest films I've ever seen (to give this claim some frame of reference I draw your attention to the fact that I have seen in excess of 17 films).

This kinda feeds from my last post in a way, as too long ago now I visited Cranforth station in Lancashire, the main setting of Brief Encounter, it wasn't planned and when the opportunity came up I was genuinely excited. When we got there, I squealed and ran around taking poorly composed photographs, and looking at memorabilia, and strongly fighting the urge to sit and watch the film that was about to begin on a small TV in the station, and drinking tea through a big soppy grin, and pretty much everyone else didn't care. It was there though that I realised just how much I really cared about this film and when I came back I gushed at folk and foisted poorly composed photos on them. They didn't care.

That said Brief Encounter is a masterpiece. A deceptively simple film that is easily dismissed on a cursory viewing, as it seems straightforward in plot and characterisation, and the dialogue seems dated and stilted. I would argue that it is in fact a masterclass in restraint and subtlety - not simplicity - subtlety, and that subtlety and complexity go hand in hand.

To nutshell the plot a married doctor man, Alec played by Trevor Howard, and a married woman (Laura played by Celia Johnson) meet in a train station and fall in love, they embark on a once weekly, clandestine love affair, that is never consummated and must end for the sake of modesty and their respective marriages. So off Alec goes to Africa to doctor about with his family and Laura returns to hers. That's it. That's your plot, but plot is only a part of a film and how this plot is delivered is crucial to where the subtlety and complexity align.

This kinda feeds from my last post in a way, as too long ago now I visited Cranforth station in Lancashire, the main setting of Brief Encounter, it wasn't planned and when the opportunity came up I was genuinely excited. When we got there, I squealed and ran around taking poorly composed photographs, and looking at memorabilia, and strongly fighting the urge to sit and watch the film that was about to begin on a small TV in the station, and drinking tea through a big soppy grin, and pretty much everyone else didn't care. It was there though that I realised just how much I really cared about this film and when I came back I gushed at folk and foisted poorly composed photos on them. They didn't care.

That said Brief Encounter is a masterpiece. A deceptively simple film that is easily dismissed on a cursory viewing, as it seems straightforward in plot and characterisation, and the dialogue seems dated and stilted. I would argue that it is in fact a masterclass in restraint and subtlety - not simplicity - subtlety, and that subtlety and complexity go hand in hand.

To nutshell the plot a married doctor man, Alec played by Trevor Howard, and a married woman (Laura played by Celia Johnson) meet in a train station and fall in love, they embark on a once weekly, clandestine love affair, that is never consummated and must end for the sake of modesty and their respective marriages. So off Alec goes to Africa to doctor about with his family and Laura returns to hers. That's it. That's your plot, but plot is only a part of a film and how this plot is delivered is crucial to where the subtlety and complexity align.

On it's release it was considered to be just an escapist love story and had only modest success. Later it was derided by a more sexually permissible 1960s crowd, where 'One critic defined the message of Brief Encounter as "Make tea, not love," and recalled how an art-house audience in 1965 jeered at Alec and Laura's middle-class torments' (Adrian Turner, 2000). Later still it is seen as 'one of the most vivid and impassioned doomed romances ever committed to celluloid.' (Timeout, 2007)

The romance of the film is effective, and indeed a friend of mine will only believe that version of events in the film is the true intent as it is one of her favourites too, but this to me is all a beautifully rendered cover for the real subject. This film is delivered in such a beautiful, deceptively simple way that it is open to numerous interpretations; varied interpretations that don't negate each other. That is a spectacular achievement and a colossal strength.

The film's narration is strongly restricted to our lead Laura, Celia Johnson's performance is electric and key to the how well the whole thing works; she is elegant, fragile and compelling. The whole film comes through her and here is where it becomes complex - She's no happy and she is at best bored and at worst depressed, so can Laura's perception of events be reliable? Is she romanticising every detail? Is she fantasying about the affair? Is she even sane, has she had an emotional breakdown? I think it is testimony to the strength of the filmmaking that any of these reading, and probably more, are supportable. Indeed Cyril Connelly once suggested that Alec isn't a doctor at all but a patient who is allowed to leave the hospital once a week and chooses to spend this time sexually pursuing vulnerable women. This is a reading I admire but don't entirely subscribe to. My own view is that he doesn't exist at all, or actually that he did help her remove coal dust from her eye at the train station but that was it. I think Laura is pulling a Keyser Söze and weaving elements from all around herself to give a weighty backstory to her fantasised romantic escapism. For example, the couple watch a trailer in the cinema for a film called 'Flames of Passion', an 'epoch-making' film where an exciting, adventurous love affair takes place in a Jungle (Africa maybe?), the trailer is followed by an advert for prams and so family is firmly brought back to the fore for Laura. Then later, after seeing 'Flames of Passion' Laura speculates "D'you know, I believe we should all behave quite differently if we lived in a warm sunny climate all the time. We shouldn't be so withdrawn and shy and...difficult." Ultimately her fantasy man moves to Africa with his family, a life she would desire perhaps if things were different? This 'fantasy' reading is the reading I personally subscribe to, the whole film arguably (well a good lump of it) takes place in the mind of the main character, hence the restricted narration, and if that's the case then anything goes in terms of representation, any character can become a manifestation of Laura's psyche; her yearnings, her passions and (importantly) her guilt.

This guilt is where I feel the film is at it's most biting, it's most savage. David Thompson says that 'the [film's] set-up begs for satire' (2010), I say the film is satire - it is subversive. It shows how a human being can be emotional destroyed by guilt and societal pressure and it is genuinely shocking. The middle/upper classes are being criticised for their attitudes towards sex and relationships and how those attitudes become dominant and dangerous. The timidity of Celia Johnson's Laura in her approach to the affair is perfectly understandable; a reaction of a bored, married woman in 1945, who has a strong attraction to a [stylised fantasy of a] married man, but I think it is arguable that film functions as an allegory of the attitudes to sexuality in Britain. This is another great strength, and a less selfish reason I felt it may be relevant to write about this film now as we have just recently 'given' rights of marriage to same sex couples.

This guilt is where I feel the film is at it's most biting, it's most savage. David Thompson says that 'the [film's] set-up begs for satire' (2010), I say the film is satire - it is subversive. It shows how a human being can be emotional destroyed by guilt and societal pressure and it is genuinely shocking. The middle/upper classes are being criticised for their attitudes towards sex and relationships and how those attitudes become dominant and dangerous. The timidity of Celia Johnson's Laura in her approach to the affair is perfectly understandable; a reaction of a bored, married woman in 1945, who has a strong attraction to a [stylised fantasy of a] married man, but I think it is arguable that film functions as an allegory of the attitudes to sexuality in Britain. This is another great strength, and a less selfish reason I felt it may be relevant to write about this film now as we have just recently 'given' rights of marriage to same sex couples.

Far from being stuffy and frigid, this film constantly references sex. Nothing in cinema is an accident - even accidents (as there must always be a decision made on whether or not to keep them or reshoot) and so why, in such a restricted narrative include so much interaction between the working classes in the tearoom and their relatively mundane chatter? Because they almost exclusively talk about sex. They are freer sexually, Myrtle (Joyce Carey) and Albert (Stanley Holloway) are open in their flirtations and Myrtle is divorced, again whether real or a manifestation of Laura's anxieties and passions, they show a devision of the classes attitudes to relationships and to sex.

This critique of sexual freedom can perhaps be taken further, the writer Noël Coward was a discreetly gay, high profile British man. In a Britain where it was illegal to be homosexual - illegal to be who you are and to the eternal shame of this country it would remain so right up until 1967. This forced many to suppress their own desires for fear of how society would judge and punish them. The societal attitudes, particularly of the middle/upper classes was repressive and this could be exactly what Coward and Lean are working towards here.

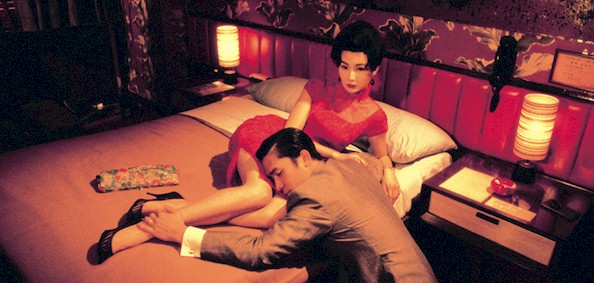

The film's genius can also be seen by how massively influential it is. It has been spoofed, remade and borrowed from by a variety of artists. Wong Kar-Wai essentially borrowed all that makes this film important for 'In the Mood For Love' (2000) which is another personal favourite of mine and pushes the use of the environment and visual aesthetic over character and plot to represent the same kind of social/cultural sexual repression/suppression. Mere love stories rarely become so beloved and both films I would urge you to watch (really watch).

The film's genius can also be seen by how massively influential it is. It has been spoofed, remade and borrowed from by a variety of artists. Wong Kar-Wai essentially borrowed all that makes this film important for 'In the Mood For Love' (2000) which is another personal favourite of mine and pushes the use of the environment and visual aesthetic over character and plot to represent the same kind of social/cultural sexual repression/suppression. Mere love stories rarely become so beloved and both films I would urge you to watch (really watch).

A final thing to think about is that it doesn't really matter so much what Coward or Lean's intention were and even less does it matter what I have to say about it, what absolutely matters is that you do not dismiss films for their apparent 'simplicity' but engage with them, give them your attention and bring to your conclusions what you feel based on what you have experienced through the piece and through everything else. Any and all of the above readings do not mean that this film is not the greatest love story ever told, they hopefully just demonstrate that a film need not be just about the things that happen in it, and if something is art it is not tied to the period in which it is created.The romance of the film is effective, and indeed a friend of mine will only believe that version of events in the film is the true intent as it is one of her favourites too, but this to me is all a beautifully rendered cover for the real subject. This film is delivered in such a beautiful, deceptively simple way that it is open to numerous interpretations; varied interpretations that don't negate each other. That is a spectacular achievement and a colossal strength.

The film's narration is strongly restricted to our lead Laura, Celia Johnson's performance is electric and key to the how well the whole thing works; she is elegant, fragile and compelling. The whole film comes through her and here is where it becomes complex - She's no happy and she is at best bored and at worst depressed, so can Laura's perception of events be reliable? Is she romanticising every detail? Is she fantasying about the affair? Is she even sane, has she had an emotional breakdown? I think it is testimony to the strength of the filmmaking that any of these reading, and probably more, are supportable. Indeed Cyril Connelly once suggested that Alec isn't a doctor at all but a patient who is allowed to leave the hospital once a week and chooses to spend this time sexually pursuing vulnerable women. This is a reading I admire but don't entirely subscribe to. My own view is that he doesn't exist at all, or actually that he did help her remove coal dust from her eye at the train station but that was it. I think Laura is pulling a Keyser Söze and weaving elements from all around herself to give a weighty backstory to her fantasised romantic escapism. For example, the couple watch a trailer in the cinema for a film called 'Flames of Passion', an 'epoch-making' film where an exciting, adventurous love affair takes place in a Jungle (Africa maybe?), the trailer is followed by an advert for prams and so family is firmly brought back to the fore for Laura. Then later, after seeing 'Flames of Passion' Laura speculates "D'you know, I believe we should all behave quite differently if we lived in a warm sunny climate all the time. We shouldn't be so withdrawn and shy and...difficult." Ultimately her fantasy man moves to Africa with his family, a life she would desire perhaps if things were different? This 'fantasy' reading is the reading I personally subscribe to, the whole film arguably (well a good lump of it) takes place in the mind of the main character, hence the restricted narration, and if that's the case then anything goes in terms of representation, any character can become a manifestation of Laura's psyche; her yearnings, her passions and (importantly) her guilt.

This guilt is where I feel the film is at it's most biting, it's most savage. David Thompson says that 'the [film's] set-up begs for satire' (2010), I say the film is satire - it is subversive. It shows how a human being can be emotional destroyed by guilt and societal pressure and it is genuinely shocking. The middle/upper classes are being criticised for their attitudes towards sex and relationships and how those attitudes become dominant and dangerous. The timidity of Celia Johnson's Laura in her approach to the affair is perfectly understandable; a reaction of a bored, married woman in 1945, who has a strong attraction to a [stylised fantasy of a] married man, but I think it is arguable that film functions as an allegory of the attitudes to sexuality in Britain. This is another great strength, and a less selfish reason I felt it may be relevant to write about this film now as we have just recently 'given' rights of marriage to same sex couples.

This guilt is where I feel the film is at it's most biting, it's most savage. David Thompson says that 'the [film's] set-up begs for satire' (2010), I say the film is satire - it is subversive. It shows how a human being can be emotional destroyed by guilt and societal pressure and it is genuinely shocking. The middle/upper classes are being criticised for their attitudes towards sex and relationships and how those attitudes become dominant and dangerous. The timidity of Celia Johnson's Laura in her approach to the affair is perfectly understandable; a reaction of a bored, married woman in 1945, who has a strong attraction to a [stylised fantasy of a] married man, but I think it is arguable that film functions as an allegory of the attitudes to sexuality in Britain. This is another great strength, and a less selfish reason I felt it may be relevant to write about this film now as we have just recently 'given' rights of marriage to same sex couples.

Far from being stuffy and frigid, this film constantly references sex. Nothing in cinema is an accident - even accidents (as there must always be a decision made on whether or not to keep them or reshoot) and so why, in such a restricted narrative include so much interaction between the working classes in the tearoom and their relatively mundane chatter? Because they almost exclusively talk about sex. They are freer sexually, Myrtle (Joyce Carey) and Albert (Stanley Holloway) are open in their flirtations and Myrtle is divorced, again whether real or a manifestation of Laura's anxieties and passions, they show a devision of the classes attitudes to relationships and to sex.

This critique of sexual freedom can perhaps be taken further, the writer Noël Coward was a discreetly gay, high profile British man. In a Britain where it was illegal to be homosexual - illegal to be who you are and to the eternal shame of this country it would remain so right up until 1967. This forced many to suppress their own desires for fear of how society would judge and punish them. The societal attitudes, particularly of the middle/upper classes was repressive and this could be exactly what Coward and Lean are working towards here.

The film's genius can also be seen by how massively influential it is. It has been spoofed, remade and borrowed from by a variety of artists. Wong Kar-Wai essentially borrowed all that makes this film important for 'In the Mood For Love' (2000) which is another personal favourite of mine and pushes the use of the environment and visual aesthetic over character and plot to represent the same kind of social/cultural sexual repression/suppression. Mere love stories rarely become so beloved and both films I would urge you to watch (really watch).

The film's genius can also be seen by how massively influential it is. It has been spoofed, remade and borrowed from by a variety of artists. Wong Kar-Wai essentially borrowed all that makes this film important for 'In the Mood For Love' (2000) which is another personal favourite of mine and pushes the use of the environment and visual aesthetic over character and plot to represent the same kind of social/cultural sexual repression/suppression. Mere love stories rarely become so beloved and both films I would urge you to watch (really watch).

Ta, J

Comments

Post a Comment