Visual Patterns: Touch of Genius

By the age of 28 Orson Welles had made his first film and that film would come to define and, arguably, haunt him for the rest his career and perhaps his life. A career dogged by unfinished projects, visions revisioned by studios and a reputation for being 'difficult' (which is what people call you if they think you're a c*nt but also want to hedge their bets), his later films were often lost in development hell and/or funding droughts. Some might say that he peaked right off the bat, personally I'm not one of them, but as he said himself, "I started at the top and worked my way down." Contracturally that may have been true but arguably not in creative terms.

His first film was Citizen Kane (1941) and is a towering piece of work, influential, experimental and controversial. It frequently tops critics best film lists and is know to most people who have seen films with an regularity. Getting those same people to name three other films he made might not be so easy, but he did make some fantastic works long after Kane; F for Fake (1973), Mr.Arkadin (1955), The Trial (1962), The Lady from Shanghai (1947) and the many...well, two - but hey! relatively speaking that's a lot...adaptations of Shakepeare, Macbeth (1948) and Othello (1952) but to try to illustrate the level of filmmaking this man operated on I'll look to a studio piece that he made and how he circumvented it to make a wonderful piece of cinema. Aspects of Welles' filmmaking that are particularly striking for me in this movie are his performance, his technical direction and his dialogue. The film is Touch of Evil (1958) and it was no smooth ride either, but as Chilli Palmer (John Travolta) says of the film in Get Shorty (Barry Sonnenfeld, 1995) "Sometimes you do your best work with a gun to your head."

The camerawork in the film is as bravara (that's a word!) as any other he ever made, with a trademark use of angles; exaggerated high, low and canted frames are everywhere and make it impossible not think about the characters. He's not afraid to move the camera, as the opening scene shows, and this cuts out the need for excessive...well...cuts, and it has the added advantage of letting the performances flow.

Welles' performance does just that, he mumbles his way through the film and seemingly loses the other actors occasionally as he talks over them in a fantastically natural way. This, coupled with shooting style, makes the whole thing seem hyper-real and allows him the scope to do pretty much anything. Some of the characters seem almost like cartoons, take the fantastic Uncle Joe Grandi (Akim Tamiroff) for example whose wig falls off whenever he tries to be menacing. Welles doesn't shy away from the humour infact he seems to inject great swathes of it throughout the film.

He supposedly worked under some duress in making this film but it doesn't show. It feels like he's having a ball. The humour is fantastic and doesn't counteract the sleaziness of the characters or events but amplifys it. It's also one of the main elements that makes the film such a fantastic piece of entertainment. Having a pop at Charlton Heston's apparent refusal to be anything approaching Mexican, Welles pipes up: "That's his wife? She doesn't look Mexican either." The humour is not reserved for others, he extends it to himself on several occasions, as there are plenty of pops at his weight, my favourite being an excellent extreme low angle shot that frames Welles and a stuffed bull's head mounted on the wall behind him. It works great as a visual parallel between the two and as a sinister portent of doom.

The film is much deeper than a mere string of gags or even a standard crime thriller. It's 1958 and we are dealing with subject matter that includes drug abuse, rape, moral corruption, racism and, arguably, homeland security. Quinlan (Welles' character) is disgusting both physically (unshaven, sweaty, crumpled, bloated, and snarling) and morally (racist, greedy and corrupt). The film works beautifully as a metaphor, layering masks and facades, for the abuses of the powerful over those considered weaker (either physically or economically, or politically) and how that power can corrupt. This is perhaps backed up by the changes Welles made to the source material, Badge of Evil by Whit Masterson. The original material has an American as the hero, with a Mexican wife. Welles reverses making a Mexican, married to an American, stand against an American and win. Welles constructs a gem (I think it's a sapphire) of pure cinema, supplying characterisation, background, and emotion through technical codes and mise-en-scène rather than directly through the dialogue, which is good in it's own way but doesn't just lazily forward plot.

This film was a return to Hollywood for Welles after a period in Europe where very few projects got off the ground. He reportedly only received an actor's fee for co-starring, writing and directing this piece. The studio then butchered his final cut, prompting Welles to write a 58 page memo asking for certain changes to be reinstated (including the soundscape mentioned earlier). The final words of which allude to the style of filmmaking that Welles favoured: 'I close this memo with a very Ernest plea that you consent to this brief visual pattern to which I gave so many long days of work.' (Orson Welles, 1957)

These wishes were finally met in 1998 (a longer cut was released by the studio in 1976 but Welles was not consulted) when a version was constructed that follows the instructions included in this memo and so now, hopefully, a version exists that is close to the film that Welles himself had planned. It is pointless to rue the level of Welles output or muse on the projects that might have been, much better to rejoice in what we do have and this is an excellent place to start. A great technician, director, writer and actor, despite being 'difficult', the relatively few works that he did leave behind have arguably enriched cinema and at the very least given us one of the great characters of the artform. I leave this post in his words (some of which are spoken by the beautiful Marlene Dietrich).

"Everybody denies that I am a genius - but nobody ever called me one."

"The best thing commercially, which is the worst artistically, by and large, is the most successful."

His first film was Citizen Kane (1941) and is a towering piece of work, influential, experimental and controversial. It frequently tops critics best film lists and is know to most people who have seen films with an regularity. Getting those same people to name three other films he made might not be so easy, but he did make some fantastic works long after Kane; F for Fake (1973), Mr.Arkadin (1955), The Trial (1962), The Lady from Shanghai (1947) and the many...well, two - but hey! relatively speaking that's a lot...adaptations of Shakepeare, Macbeth (1948) and Othello (1952) but to try to illustrate the level of filmmaking this man operated on I'll look to a studio piece that he made and how he circumvented it to make a wonderful piece of cinema. Aspects of Welles' filmmaking that are particularly striking for me in this movie are his performance, his technical direction and his dialogue. The film is Touch of Evil (1958) and it was no smooth ride either, but as Chilli Palmer (John Travolta) says of the film in Get Shorty (Barry Sonnenfeld, 1995) "Sometimes you do your best work with a gun to your head."

A lot is said of the opening shot which introduces us to a political situation, two of our main characters and the world they inhabit. All in a single, 3 minute and 18 second crane shot, that pans and tracks and tilts and peds all over the shop. The shot itself is complex and works very well, but for me the power of the scene comes from the fantastic soundscape Welles creates throughout (something the studio tried to excise in favour of a non-diegetic theme tune, in their ill-advised recut of the film) that actively pulls you into the environment and gives you a feeling of the diversity and atmosphere of the border town. If your ears could talk (can you imagine that!? that'd be really confusing) this is what they'd call out for, and they wouldn't let you get any sleep or listen to any post-punk-pop-rock or whatever until they'd had it in them.

The camerawork in the film is as bravara (that's a word!) as any other he ever made, with a trademark use of angles; exaggerated high, low and canted frames are everywhere and make it impossible not think about the characters. He's not afraid to move the camera, as the opening scene shows, and this cuts out the need for excessive...well...cuts, and it has the added advantage of letting the performances flow.

Welles' performance does just that, he mumbles his way through the film and seemingly loses the other actors occasionally as he talks over them in a fantastically natural way. This, coupled with shooting style, makes the whole thing seem hyper-real and allows him the scope to do pretty much anything. Some of the characters seem almost like cartoons, take the fantastic Uncle Joe Grandi (Akim Tamiroff) for example whose wig falls off whenever he tries to be menacing. Welles doesn't shy away from the humour infact he seems to inject great swathes of it throughout the film.

He supposedly worked under some duress in making this film but it doesn't show. It feels like he's having a ball. The humour is fantastic and doesn't counteract the sleaziness of the characters or events but amplifys it. It's also one of the main elements that makes the film such a fantastic piece of entertainment. Having a pop at Charlton Heston's apparent refusal to be anything approaching Mexican, Welles pipes up: "That's his wife? She doesn't look Mexican either." The humour is not reserved for others, he extends it to himself on several occasions, as there are plenty of pops at his weight, my favourite being an excellent extreme low angle shot that frames Welles and a stuffed bull's head mounted on the wall behind him. It works great as a visual parallel between the two and as a sinister portent of doom.

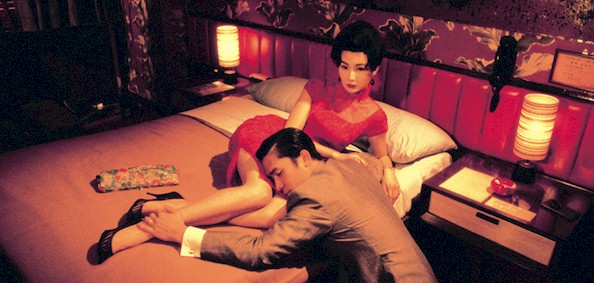

The film is much deeper than a mere string of gags or even a standard crime thriller. It's 1958 and we are dealing with subject matter that includes drug abuse, rape, moral corruption, racism and, arguably, homeland security. Quinlan (Welles' character) is disgusting both physically (unshaven, sweaty, crumpled, bloated, and snarling) and morally (racist, greedy and corrupt). The film works beautifully as a metaphor, layering masks and facades, for the abuses of the powerful over those considered weaker (either physically or economically, or politically) and how that power can corrupt. This is perhaps backed up by the changes Welles made to the source material, Badge of Evil by Whit Masterson. The original material has an American as the hero, with a Mexican wife. Welles reverses making a Mexican, married to an American, stand against an American and win. Welles constructs a gem (I think it's a sapphire) of pure cinema, supplying characterisation, background, and emotion through technical codes and mise-en-scène rather than directly through the dialogue, which is good in it's own way but doesn't just lazily forward plot.

This film was a return to Hollywood for Welles after a period in Europe where very few projects got off the ground. He reportedly only received an actor's fee for co-starring, writing and directing this piece. The studio then butchered his final cut, prompting Welles to write a 58 page memo asking for certain changes to be reinstated (including the soundscape mentioned earlier). The final words of which allude to the style of filmmaking that Welles favoured: 'I close this memo with a very Ernest plea that you consent to this brief visual pattern to which I gave so many long days of work.' (Orson Welles, 1957)

These wishes were finally met in 1998 (a longer cut was released by the studio in 1976 but Welles was not consulted) when a version was constructed that follows the instructions included in this memo and so now, hopefully, a version exists that is close to the film that Welles himself had planned. It is pointless to rue the level of Welles output or muse on the projects that might have been, much better to rejoice in what we do have and this is an excellent place to start. A great technician, director, writer and actor, despite being 'difficult', the relatively few works that he did leave behind have arguably enriched cinema and at the very least given us one of the great characters of the artform. I leave this post in his words (some of which are spoken by the beautiful Marlene Dietrich).

"Everybody denies that I am a genius - but nobody ever called me one."

"The best thing commercially, which is the worst artistically, by and large, is the most successful."

I had no idea Mr Welles had made so many other films after 'Citizen Kane' (which I still embarrassingly have yet to see). That crane shot was fantastic!

ReplyDelete